Robert Abbott

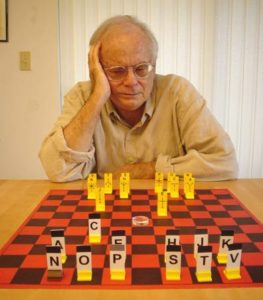

Robert Abbott has been designing games, mazes and puzzles for decades. He’s the inventor of Ultima, which was ChessVariant.org’s Recognized Variant of the Month in 2001 (only 39 years after it was originally released). He’s also the inventor of Eleusis, a card game that he considers his greatest achievement, and the author of Abbott’s New Card Games.

He’s also an authority on a genre of puzzle known as “mazes-with-rules” or “logic mazes,” his most famous creation being Theseus and the Minotaur. He’s the author of SuperMazes and Mad Mazes and has a website devoted to the subject.

We had a nice long talk with Mr. Abbott about his mazes and his history – including the unusual luck of being discovered in 1959 by a man named Martin Gardner.

Puzzle Monster: You’ve been designing games and puzzles a good long time. How did you get started?

Robert Abbott: I should say that I wouldn’t have gotten anywhere if

Martin Gardner had not discovered me. In 1959 I sent him a letter about

my card game Eleusis. This letter was from a complete unknown, someone

with no publications or academic credentials. The majority of editors

and the majority of writers wouldn’t have even read my letter. Martin

not only read my letter but he saw what was good about Eleusis. I had

mentioned that the game involved inductive reasoning, but Martin also

saw that the game could be an analogy for the scientific method. He

devoted his next Scientific American column to Eleusis, and the game

became quite popular.

PM: Besides developing games, did you have a day job?

RA: Because I wanted to invent games (or do something creative), I

didn’t want a job-type job. Mostly I worked as a typist. But then I got

tired of being poor, so in 1964 I got a job as a computer programmer.

Programming was a revelation to me. It was more fun than any of my

“creative” work. The most fun I had was at the Bank of New York. A group

of us created a teleprocessing system using the 360 assembler language

and BTAM (Basic Telecommunications Access Method). We even created our

own language using the macro facilities of the 360 assembler.

Just about everything I’ve done since then has used programming in some

form or other. I’m now 71 years old and I can’t stop programming. The

mazes on my web site that are implemented in JavaScript are mostly there

because I was having fun with JavaScript.

PM: After the success of Eleusis in 1959 and Ultima in 1962, you became, as you put it, “entranced” with mazes, and have been designing and redefining them for forty years. Why do logic mazes hold your interest so much more than games?

RA: I think I just lost interest in games, and I’m not sure why. I probably just ran out of ideas. I also ran out of game players (moving from New York to Jupiter, Florida, was part of that problem). Also, creating great things and not getting them published is a big turn-off.

PM: You’ve said that “some mazes work best as walk-throughs, some work best in a computer program, and some even work best on the printed page.” Can you elaborate?

RA: Each medium has advantages and disadvantages. Computer programs probably work the best, and a lot of mazes-with-rules only work as a program. One advantage of programs is they make sure you follow the rules. A disadvantage of programs is you can avoid any thinking by just fiddling with the controls until you chance upon the solution. Another disadvantage occurs when you have a large team of programmers, graphic designers, music composers, and a couple of million dollars to spend on the program. This produces programs with excessive graphics that make it impossible for the player to use any logical thinking, and this is why none of the current video games are as good as the video games produced in the 1970s and 1980s.

Conventional mazes are exciting, but the only way to experience them is in a full-size walk-through. On paper, they are only interesting for small children. And have you seen computer programs that try to present a first-person view of traveling through a maze? It just doesn’t work; though it’s hard to explain why.

Walk-through mazes-with-rules are also exciting. As far as I know there are only two people working with them: me and Adrian Fisher. I did, however, get Andrea Gilbert to create one, which was based on her Tilt Mazes. It was built next to some of the cornfield mazes.

Walk-through mazes-with-rules are also exciting. As far as I know there are only two people working with them: me and Adrian Fisher. I did, however, get Andrea Gilbert to create one, which was based on her Tilt Mazes. It was built next to some of the cornfield mazes.

The least exciting medium for mazes-with-rules is the printed page. But it’s still pretty good. In addition to just the printed page, there can be dice that roll through the maze, there can be coins that are pushed through the maze, and there can be a page that slides over another page, causing changing configurations of the maze.

PM: Some of your walk-through mazes-with-rules, such as the Bureaucratic Maze, are fairly radical because they have no walls. At what point does a maze cease to be a maze? For example: is NerdCon a maze or a puzzle? It’s similar to Bureaucratic Nightmare – which is clearly a maze, since it’s adapted from your own – but it has some potentially significant differences.

RA: This brings up a very interesting point. There are games and puzzles that, on the surface, look very different from each other, but they contain the same underlying principle.

NerdCon and the Bureaucratic Maze follow in a line that goes back to the Colossal Cave, which was part of Adventure, the first adventure program. It was written in 1972 by William Crowther, and it ran on the PDP-10. For a complete history, see this page. The Colossal Cave was a maze with this underlying principle: what entrance you take into a room determines what exits you can take out of the room. It is therefore a multi-state maze. The state you are in is not just determined by where you are but also by how you got there.

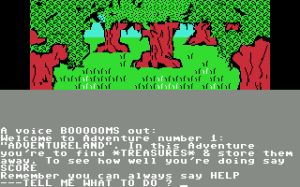

After personal computers appeared, there were many adventure programs. The one that I played (for many months) was Adventureland, written for the TRS-80 by Scott Adams. Every one of these programs had a maze similar to the Colossal Cave (but towards the end of the 1990s, along with greater use of graphics, these mazes appeared less frequently).

After personal computers appeared, there were many adventure programs. The one that I played (for many months) was Adventureland, written for the TRS-80 by Scott Adams. Every one of these programs had a maze similar to the Colossal Cave (but towards the end of the 1990s, along with greater use of graphics, these mazes appeared less frequently).

In 2000 I had what I thought was a brilliant idea: if kids liked the mazes in adventure games, they would really like a version that they could actually walk through. I created something I called The Dungeon Maze. It had four rooms with five corridors making connections between the rooms. When you enter a room, you pass by a sign that says something like “Take Exit 1 or Exit 3,” and once inside the room you see signs identifying the various exits. With only four rooms, it sounds like it would be simple, but it was actually very complicated.

The Dungeon Maze was implemented a few places in 2000 as part of my small courtyard mazes outside large cornfield mazes. The implementations weren’t very good. One used strings on poles to define the rooms. One cut the rooms out of a corner of the cornfield, but the rooms weren’t made large enough. I still think this is a brilliant idea and I hope someday it will be realized in a better form. I think it could work well as part of a haunted house attraction.

After working on The Dungeon Maze, I thought of another way to use the same underlying principle. I created The Bureaucratic Maze, something that doesn’t look like a maze at all. In it, you carry forms from desk to desk. The forms have information about what desk you came from and what choice you have of desks you can go to. When you arrive at a desk, the “bureaucrat” at that desk gives you another form, and what form he gives you depends on what desk you just came from. Therefore, at any desk you are in different states, depending on which desk you came from. This is the same as the Colossal Cave: in any room you are in different states, depending on what room you came from.

I never thought The Bureaucratic Maze could be very popular, but a lot of people are interested in it, and you turned it into the hilarious Bureaucratic Nightmare. Again, there’s the same underlying principle, but instead of different forms there are different pop-up windows (and also, you don’t need several volunteers to act as bureaucrats plus many copies of the forms).

I never thought The Bureaucratic Maze could be very popular, but a lot of people are interested in it, and you turned it into the hilarious Bureaucratic Nightmare. Again, there’s the same underlying principle, but instead of different forms there are different pop-up windows (and also, you don’t need several volunteers to act as bureaucrats plus many copies of the forms).

This will confuse this history, but I can’t resist adding that I used something like this underlying principle in a maze that predated the Colossal Cave. My maze was in the October 1962 Scientific American (and there’s an improved version here). Instead of rooms, I had intersections, and how you entered an intersection determined how you could leave it. I have no idea whether William Crowther saw this maze before he created the Colossal Cave.

PM: What kind of puzzles do you like to solve when you’re not creating your own?

RA: I used to do a lot of logic puzzles (my wife and I used to go through every issue of Dell Logic Puzzles). But now I mostly do just maze-type puzzles. My favorites are those by Andrea Gilbert and James Stephens.

PM: The last book you published was SuperMazes in 1997. Can we look forward to anything coming out in the near future?

RA: I’m currently trying to get a publisher for my game Confusion. I’m also starting work on a computer program that will involve a series of mazes. This program could be revolutionary (well, maybe). I hope I can find a publisher for the program, but that may not happen.

************************************************************

Note: This interview originally appeared on Puzzlemonster.com in November of 2004. It has had a minor update.